The remnants of war

Eighty years after the start of the Spanish Civil War, we trace what is left of the brutal fratricidal conflict that tore Spanish society apart

It has been 80 years and many who lived through it are no longer with us, yet the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) remains alive in our collective memory. The most obvious traces of the war are the material remains, and every so often a reminder of the conflict is unearthed, whether an unexploded shell or a long buried air-raid shelter.

What's more, the efforts to recover and preserve the most emblematic remains of the fratricidal conflict have been stepped up. In particular, information centres have been opened to inform an increasingly distant public of the war's key events, from the Battle of the Ebre to the march into exile.

The first part of the following report focuses on the war's material remains, with an overview of some of key sites: air-raid shelters, infrastructure, traces of the exile and the Ebre battleground. Recently, many of these places have been restored, signposted or equipped with information centres.

Yet, the report also attempts to track a more ephemeral aspect of the war: the personal and collective memories, essential for understanding the conflict.

Eighty years have passed, but the Civil War is still like an old suitcase waiting to be unpacked. One reason is that for decades the only memory allowed was that of the victors. Meanwhile, for years an institutional silence has reigned, as part of the effort of avoiding opening old wounds. The result is that official memory lags behind that of the historians who have documented the events and the testimony of the participants. In fact, only in the past decade has an institutional effort been made to recover the memory of the war, with the creation of organisations like Memorial Democràtic. The war may go back eight decades, but its aftermath is still far from over.

Remains of Republican military might

Traces of the Republican military infrastructure still remain and can be visited, particularly the network of airfields with their hangars, trenches, anti-aircraft defences and bunkers

Apart from air-raid shelters, are other material traces of the Civil War infrastructure still remain, such as trenches, anti-aircraft defences, barracks and bunkers, some of which are open to the public. One of the most interesting places is in the park in Martinet i Montellà, which allows visitors to visit eight different types of bunker, including machine gun nests, underground passageways and artillery pillboxes, on a signposted itinerary to guide visitors.

Much of the effort to make civil war military infrastructure open to the public has focused on air force facilities. Republican commanders created a network of small aerodromes for their squadrons of Tupolev bombers and Polikarpov fighter planes. Depending on their importance, the airfields were categorised as permanent, semi-permanent or temporary, and some of these facilities were even later re-used by the victorious Francoist forces.

Logically, few of the temporary airfields survive today, as they have been largely turned into farmland or urban centres. However, there are still a few in existence, such as those in Pla de Martís (Esponellà in Pla de l'Estany) or Celrà (Gironès). Meanwhile, those in the other categories are more common and are often signposted, such as that in Aranyó near Cervera, while some of the more permanent aerodromes have become the centre of entire museum projects. One of great strategic importance was that in Alfés, in the county of Segrià, and today its munitions dump, air-raid shelters, barracks and hangar all still stand and can be visited as part of a signposted itinerary. Another airfield worth mentioning is that of Rosanes (Vallès Oriental), whose facilities have also been preserved and that also have a signposted itinerary as well as a number of interactive displays.

In the footsteps of the Republican exile

The victory of Franco's forces in 1939 and the fall of Barcelona saw the beginning of an exodus of half a million people seeking safety across the French border

It was Catalonia's northern frontier area near France that took the brunt of the unprecedented exodus that followed the Republican defeat in the Spanish Civil War in 1939. One of the mountain passes over the Spanish-French border that was used most by those fleeing reprisals was Belitres, while another key route was the Pertús main road between Figueres and Perpignan. It is estimated that between the end of January and the beginning of February in 1939, at least 350,000 people crossed over into France through these two points. At the same time, there were people coming the other way, as they attempted to flee Nazi-occupied Europe.

The routes used by these thousands of demoralised and desperate refugees still exist. The so-called Camí de la Llibertat, which is now signposted with both historical and environmental information, crosses through the Alt Pirineu natural park. The path passes along the Borda de Perosa route (1,480 metres) to the Pala de Clavera mountain pass (2,520) and takes about four hours to walk. On the other side of the border, in Saint-Girons, is the Chemin de la Liberté museum, which has information on the allied occupation of the town as well as about Spanish prisoners who were held there.

The main routes taken by the half a million people who fled Franco's victorious forces at the start of 1939 all go through the Alt Empordà region. The area has a number of routes related to the exodus grouped under the name of Retirada i Camins de l'Exili, which includes signposted areas in 17 towns located in the Albera and Salines massifs.

It is also worth mentioning the towns that played an important role in the evacuation, including a number of emblematic buildings, such as Mas Perxés in Agullana, which acted as the final Republican Generalitat, or the Mina Canta or Mina de Negrin, where part of the Republic's artistic heritage was kept.

One of the most iconic places related to the refugees escaping occupied France is that dedicated to the philosopher Walter Benjamin, who committed suicide in Portbou while attempting to fleeing Nazi persecution. His monument, located beside the cemetery, was designed by the artist Dani Karavan.

MUME

One of the ways that the tens of thousands fleeing the consequences of Franco's victory in Spain are remembered is by the Museu Memorial de l'Exili (MUME). This memorial museum in the border town of Jonquera, which opened its doors to the public in January 2008, is dedicated to remembering the Republican exodus and is one of the key venues in the network of historical sites.

However, the museum's main exhibition is dedicated to the whole concept of exile, from the start of the Spanish Civil War until the transition to democracy in the 1970s. The exhibition is split into five sections according to theme: the past and present of exile; war, defeat and withdrawal; the diaspora; experiences; and the legacy of exile. The tour combines traditional features, such as information panels and displays of original documents, with modern audiovisuals. In all, it allows for different levels of interpretation while maintaining scientific and academic rigour.

Apart from this permanent exhibition, MUME also organises many temporary displays devoted to the issue of exile and diaspora, and has areas for educational workshops. As well as providing educational activities, the museum also offers guided visits of the facility.

History by the victor

The historical narrative of the Spanish Civil War has changed radically over the past eight decades

The Republic was like a concentration and alliance of all Spain's constant enemies come together to make a definitive effort against her. Napoleon, the liberal arm of the French Revolution, had returned to Spain through the Freemasons. Luther through the ungodly anti-Catholic intellectuals. The Turks through the Asiatic and destructive Bolsheviks.” This quote comes from the Manual de la Historia de España (Manual of the History of Spain) written by José María Pemán, president of the culture and education cleansing commission. This book was to become the basis for how the story of the war would be presented to schoolchildren in Spain during the years of the Franco regime.

In fact, the manual appeared even before the war had ended, but the rebels already felt the need to justify their coup and so efforts were begun early to provide the new regime's particular view of the Republic and the Civil War. That view was very black and white, and merely a question of good versus evil. The latter was represented by the Republicans, referred to pejoratively as “reds” or “Communist hordes”, while the former were Franco's supporters, represented as patriots and generally referred to as the “nationalists”.

As for its contents, the book largely focused on the military aspects. Certain glorious episodes for the victors were highlighted, such as the nationalist resistance in the Siege of the Alcázar in Toledo. Meanwhile, less flattering facts were not mentioned, such as the substantial help given the rebels by the German and Italian military forces or the Francoist repression against Republicans.

Above all, the interpretation of events was based on a systematic distortion of the Republic which, as seen above, was represented as introducing a period of hostile chaos that justified Franco's rebellion. In the Francoist version of history, the elections of 1939 had only been won by the Popular Front (the left-wing coalition led by Manuel Azaña) because of “coercion and intolerable violence”, with the Republicans seeking power in Spain only to begin a Communist revolution.

This version of events held sway in Spain until the end of the 1960s, when slight alterations to the narrative were introduced. While the threat of a Communist revolution continued to be portrayed as the justification for the rebellion and the war, more emphasis was put on the public disorder in the lead-up to the conflict, particularly in spring 1936.

Nevertheless, the Republicans were still held responsible for starting the war: “It was the same Republic that provoked the war and which, from the outset, ignored the convictions of the Spanish people: it persecuted the Church, harassed its ministers in an outrageous manner and prevented public coexistence, endangering the very existence of Spain.” There was also a change to the terminology used: the concept of crusade was removed, for example, to be replaced by less ideological terms, such as military coup.

New curriculum

However, the biggest change to the official version came with the curriculum for the Bachillerato, published in 1975. It was a curriculum approved at the tail end of the Franco regime but which remained in force until 1990. The first change was that more emphasis was given to the conflict itself in the history textbooks, while the issues to be covered in classrooms also changed, introducing such things as the international support provided to both sides or the political evolution of each faction.

However, the biggest change was in how the start of the war was dealt with. While some books continued to insist on the threat of revolution as a cause, a new interpretation began to gain ground that focused on political violence and social polarisation as factors leading to the coup d'etat.

Since then, the changes made to history textbooks have been considerable and are now in line with the latest research on the subject. Gone is the classic simplistic narrative to be replaced by material that makes use of graphics and maps to better show the complexity of the conflict.

As for context, the Spanish Civil War is now represented as linked to the existence of the Republic without portraying it is a simple relationship of cause and effect. Moreover, in the specific case of Catalonia, the textbooks include relevant data referring to both self-government and the country's own dynamics, with emphasis placed on such things as social change and postwar life.

Taking the Civil War into the classroom

The way the conflict is taught in secondary schools has changed radically over the past few years

The pupils are not passive, but active protagonists who build a narrative

Meritxell: 'The attitude of the anarchists worked against them, and lost them support'

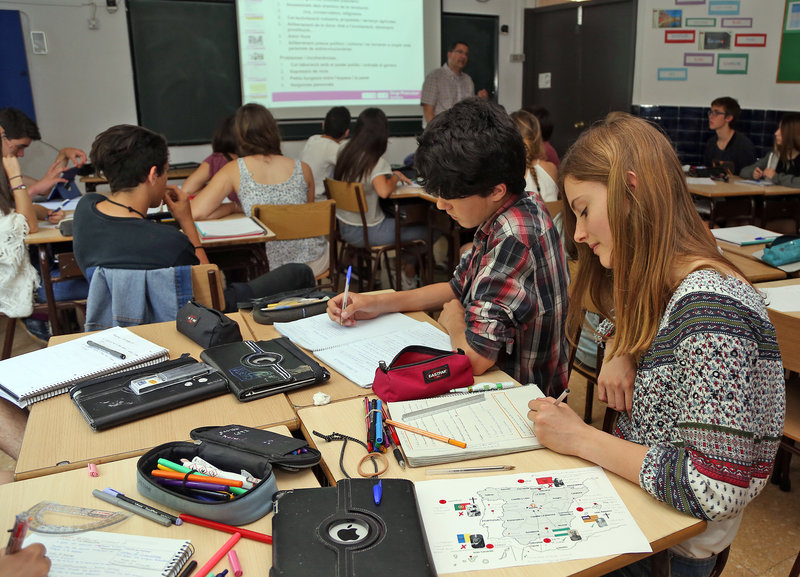

There is no longer an official version taught in schools on the conflict that tore Spain apart from 1936 to 1939. The way the Civil War is presented to the new generations has changed, both in terms of the content and the methodology. The Sadako school in Barcelona is a good example of how things have changed. We were lucky enough to be invited to witness one class at the school that dealt with the anarchist revolution in the first months of the conflict.

First of all, the classroom dynamic was completely participative. Referring to diagrams on a large screen, teacher Jordi Nomen conducted and moderated a session in which the pupils were not passive subjects, but rather active protagonists who played their part in building a narrative together.

The initial question was not easy to answer: why did the Republic lose the war? To help answer the question, the class focuses on the anarchist revolution in the first months of the war. Edgar points out that “the anarchists suddenly found themselves armed” and took advantage to impose their ideology, while Diego comments on the lack of military training of these anarchist forces sent to the front. There are constant references to the present, and the teacher brings up the concept of using assemblies as a system of collective organisation, asking the pupils which political party now uses this system. In unison some pupils cry out: “CUP!”

The class moves on to the complex subject of violence. Using a diagram on the sociological profile of the victims, the teacher attempts to situate the debate on each faction's tendency to resort to violence. However, the main part of the session is devoted to the “problems and inconsistencies” of the revolution: the role of political power and the government, the influence of personal grudges, the limitations on suppressing atrocities and the discomfort of the middle classes. The class touches on the subject of collectivisation, with one pupil defining it as “the elimination of private property and the common management of industry and farming on the behalf of the workers.” Another asks if goods were also collectivised but the teacher says it only applied to “the sharing of the means of production, to wealth creation.”

Inconsistencies

A discussion on the inconsistencies of freeing political prisoners while imprisoning detractors comes up, with Meritxell commenting that “the anarchists defended the idea that everyone thinks differently but then locked up those who thought differently from them.” This leads to a discussion on the inconsistencies of anarchism, as the class moves closer to discussing the failure of the anarchist revolution and its contribution to the Republican defeat, the question that started the class.

The teacher points out that “wars create extreme factions on both sides that cannot agree, generating inconsistencies and injustices.” This issue of opposing extremes allows the teacher to introduce another contradiction: the discomfort of the middle class when confronted with a situation of revolution. Using the example of a small business owner who has firm taken away from him despite declaring against fascism, the teacher asks how that person must feel. Carla comments on “the feeling of impotence in those Republicans who did not agree with the revolution.” Meritxell says that this is the reason why the revolution failed, and Edgar brings up a key issue: “On the Republican side, the revolution created two factions.”

Squaring the circle

The point is relevant to the original question: “Do you think that this affected the Republic? Do you think that this helped cause it to lose the war?” Carla comments on “the feeling of impotence in those Republicans who did not agree with the revolution” while Mariona suggests “they should have focused on winning the war with all the support they could get.” Meritxell adds that “the attitude of the anarchists worked against them, because it lost them support for the revolution.” At this point, the teacher lays out which groups made up the Republican side and the problems caused by personal vendettas and the subsequent violence.

The revolution lasted a mere four months and the teacher asks the pupils why. The pupils know that the answer is that the other Republican faction took power away from them, which is a taster of the next class, which will focus on the anarchist loss of influence.

An hour has gone by and the class is over, with the pupils getting the opportunity to jointly reconstruct a coherent narrative about the war. It is a complex narrative, but one that is far more sophisticated and realistic than that presented to their parents and grandparents when they were at school.