Interview

DECLAN DONNELLAN

‘If it isn’t about people then it isn’t even theatre’

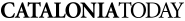

The British theatre director gives us an insight into his work as he returns to Catalonia for the Temporada Alta festival with his Russian company to perform Twelfth Night

You are a regular at the festival. How does coming back to Temporada Alta feel?

We’ve been coming to Temporada Alta for many years now. I think our first show as part of the festival was Macbeth in 2009, but we’ve been coming to Catalonia for much longer. Some of our most passionate audiences are from here and it is always a genuine pleasure to return. I think the first ever show we did in Catalonia was As You Like It in 1994 at the Mercat de les Flors in Barcelona. This year a man came up to me in Sant Cugat after the Winter’s Tale and said he had seen all our shows since the Country Wife in Edinburgh in 1981.

How did you start working with the Russian actors?

In 1987 we did Philoctetes at the Finnish National Theatre and Russian director Lev Dodin was there . We got to know Lev extremely well. The Finns do good vodka. He invited us to the Maly Theatre to see his company (which had not been performed outside of Russia at this point). They performed a six-hour epic production called Brothers and Sisters and both Nick and myself thought it was the best thing we had ever seen in our lives. Lev became a great friend and his company also started touring – so Cheek by Jowl and the Maly company would often be playing in the same theatre or festival on the circuit. He asked us to do a show for him at the Maly – and in 1997 we went and did The Winter’s Tale with the Maly actors. It was the same company of actors who we had seen in Brothers and Sisters, and our Russian Winter’s Tale is still running!

How do you go about tackling the work of such a big name as Shakespeare?

When starting on a Shakespeare play, I find it best to approach it with a sense of humility and curiosity. I think through the text he takes us by the hand into amazing worlds. Shakespeare’s language is the rocket ship by which we travel to these amazing worlds. If Shakespeare’s play does not seem transgressive, then his spirit has been betrayed. The most extraordinary thing about Shakespeare, and why we perform him so much, is that he speaks to us very clearly about how we deceive ourselves and he cuts straight to the quick of the human experience, something that is ‘timeless’ and something that is ‘universal’. These words sound like clichés and I dread using them, but they are in fact true! At the centre of his work is a permanent investigation of human love, but as there can be no love without loss, he has to talk about loss too. He talks to us about these overwhelming obsessions which are as relevant today as they were 400 years ago, and as they will be in another 400 years’ time. Above all Shakespeare understands that a human being is an animal who is inauthentic. We are all puppets and we need to make sure we were pulling our strings. And men tell us the opposite. They tell us that we are sad if we are inauthentic and that we will no longer be fake if we buy their product. The slogan for shampoo “because you’re worth it” implies the precise opposite. Viola shares a line with Iago: “I am not what I am.” They are both fakes, fakes like all of us!! Yet, just because we are all constructed does not mean we have the right to lie. We can never tell the truth about ourselves because we do not know it. But we can choose what we do and we can choose not to lie. This is the big theme that obsesses Shakespeare.

How does working in Russian theatre compare to working in British theatre?

Fundamentally, I don’t really believe that individual actors are so different in the Russian or English speaking world. The challenges that the actors face are the same. However the systems in which they work are very different. In England we have a very rigid system – because of the way contracts work. With English actors we are only able to use the beginning of our rehearsal period to experiment and try different ideas with the company. However, with our Russian (and French) company we can have an experimental period well in advance of the rehearsals. We have never really seen language as a barrier. Really these ‘barriers’ vanish once you realise that words are only a small part of how we communicate. In Russia, it is true, we are dependent on brilliant interpreters; we also have a native Russian speaker as our Assistant Director – Kirill Sbitnev has assisted us on Measure for Measure as well as The Tempest – and has now taken over on Twelfth Night. With Shakespeare – even in English language productions – we do a lot of movement work while considering the delivery of the verse. However, the rules to this should be both few and good! But it’s the movement that is very important – the verse is best rediscovered through movement. We have been going to Russia since Soviet times and have worked there so often and have such close relationships with the people there that in truth, we feel part Russian. Incidentally Russians adore Shakespeare as well as their own national classics, such as Pushkin, Chekhov, and Tolstoy.

What advice would you give a young director looking to make a career in theatre?

I talk to a lot of young people coming into the theatre and very often they tell me they’re confused about theatre and are sometimes frightened because they are confused. They are sometimes frightened because of their desire and of course their desire is the important thing about them. The function of life is not to conquer desire; that is our life. They get very confused about the ‘look’ their work should have and very often I feel sad because they want to know how their work should look to be ‘fashionable’. Sometimes they succeed for a little while and sometimes they don’t. I think all I can say now is that it’s important to look at what endures. When we put on a piece of theatre, we are a group of people looking at other people doing something and that couldn’t be more important. Its impotent politically. We are facing frightening times and we need to develop our empathy. Politicians and priests feel that they need to tell us the truth and they have to have a solution to the problem. But we who work in the theatre do not have this problem. Because we don’t have to tell the truth and we must never delude ourselves that we are telling the truth. We are making an illusion and the illusion is a means to help us be empathic to another world. We make ourselves weak if we pretend we know the solution; we must make the illusion the best we can, as responsibly as we can. Another thing that makes me sad about young directors sometimes is when I ask them how many things they are doing that year, and they often say four or five things and they don’t see them after they open. This makes me sad because I’d like to think that more young directors thought it was their job to look after the acting. I’d like to think I’ve always thought that the actor’s art was the first and last word in theatre but it needs a strong director to organise that and to make sure it takes place at the right levels of philosophy, politics and spirituality to make sure the intimacy is being connected with. I think that good theatre needs to be strong visually and sometimes I see young directors frightened of the humanity and focusing more and more on the strong visual impact of their work. All I would say is that theatre is weak if it isn’t strong visually. But if theatre isn’t about people then it isn’t even theatre.

Is there a production you have never done but would one day love to direct?

I spend my life trying to find it!

Leave a comment

Sign in.

Sign in if you are already a verified reader.

I want to become verified reader.

To leave comments on the website you must be a verified reader.

Note: To leave comments on the website you must be a verified reader and accept the conditions of use.