Tales of EXILE

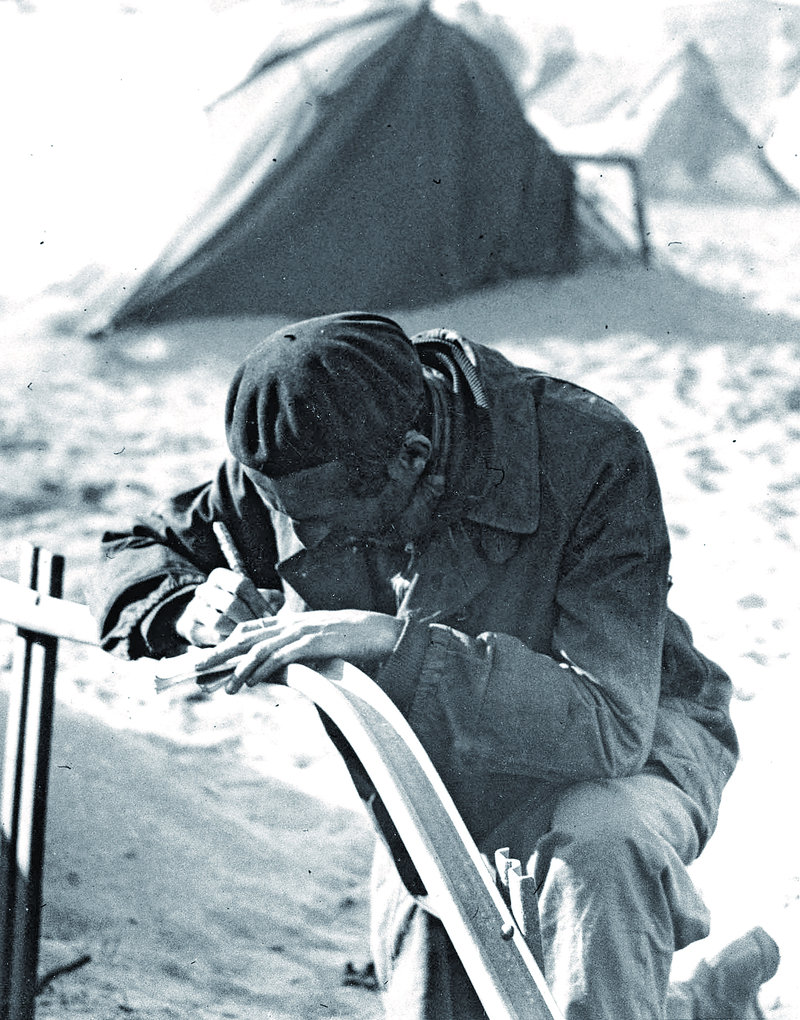

On February 5, 1939, the French authorities opened the border to the exiles concentrated on the other side. What follows are testimonies of those who experienced the tragedy

On February 5, 1939, after crossing the French border, the Figueres politician and historian, Alexandre Deulofeu, wrote: “I feel invaded by nostalgia for our land [...]. We see the line between France as our salvation. Today that line separates two different worlds. One of them, ours, is hostile to us, and if we do not get away, we will end up dead. The other is free Europe, democracy, freedom, respect for humanity. With hearts broken over leaving our land, we enter France like someone embracing salvation.”

Despite the hopeful words from the mayor of Figueres, France did not exactly provide salvation. An uncertain future awaited the 400,000 republican refugees who crossed the French border. For some of them, exile became the entryway into the hell of the Argelers internment camp, and worse for some, a few months later the Nazi concentration camps. Meanwhile, others exchanged a civil war for a world war and a seemingly interminable struggle against the barbarism of fascism. For the rest of them, it led to a new life on French soil, or even on the other side of the Atlantic.

There had been a constant stream of people choosing to go into exile throughout the Civil War, especially in the first few weeks, although most were people fleeing revolutionary violence, or trying to reach territory held by the rebel military. However, from December 23, 1938, when Franco’s troops launched the final offensive against Catalonia, the trickle of exiles became a full-blown exodus. To the human drama of the local civil population was added that of thousands of refugees who had been steadily arriving since the outbreak of the war, and who amounted to more than 700,000 by the middle of 1938. After the fall of Barcelona, the chaos spread throughout the rest of Republican held territory, and all the roads leading to France became unending rivers of people burdened by their personal possessions.

In his personal diary, Antoni Rovira i Virgili wrote: “Carts piled high with furniture, mattresses and even bird cages. Each cart is a family that is leaving; each line of carts is an empty village.” A large part of these possessions would be abandoned at the side of the road and the exiles would cross the border with just a few suitcases or even just what they could carry in their pockets. Added to the toughness of the journey and the poor weather conditions were the attacks by Franco’s troops, who until the last moment continued to bomb the civilian population in a final act of merciless repression.

Catalonia had long been familiar with political exile, ever since the War of Spanish Succession in the 18th century. The largest event of that kind up to that point had been seen during First Carlist War, back in 1840, when some 20,000 men, both soldiers and refugees, sought safety in France. However, the numbers involved in 1939 at the end of the Civil War were of another order and the experience left deep collective scars, to which must be added the repression suffered by those who chose to remain in a beaten and defeated country.

One of the best studies on the issue was by historian Javier Rubio, who estimated that almost 470,000 people crossed the border in January and February 1939. Some of them would return in the years that followed, but others never did. The drama experienced in 1939 has echoes in the refugee crisis Europe has undergone in the past few years and, from a personal point of view, in the pro-independence leaders transferred to Madrid to stand trial.

feature

The exodus in numbers

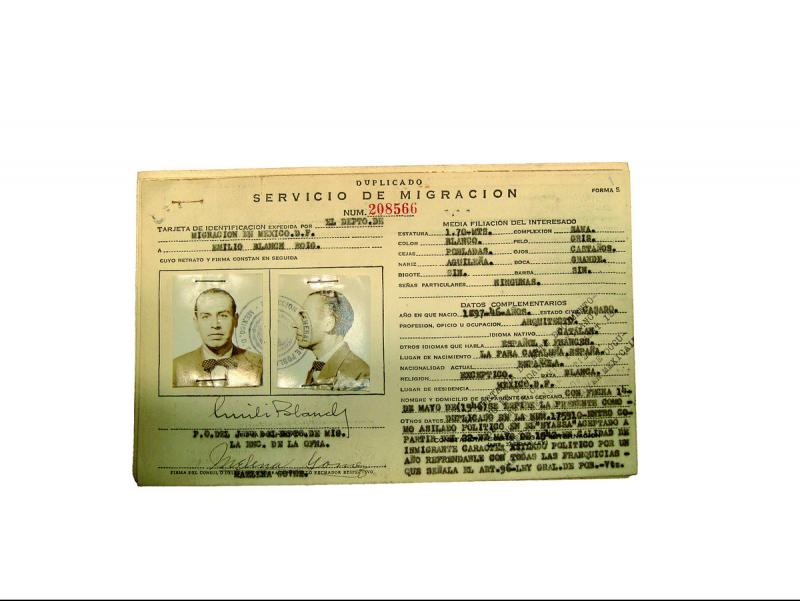

A report by the Franco-Mexican Commission put the number of refugees who had fled to France at 500,000 exiles. Of the Catalan people who went into exile, some 50,000 - among whom there were a larger number of intellectuals - were later evacuated to other countries. Most of the exiles who moved on to another country after crossing the French border eventually found themselves in Latin American countries, especially Mexico, where between 18,000 and 30,000 republicans found refuge.