Downright peculiar

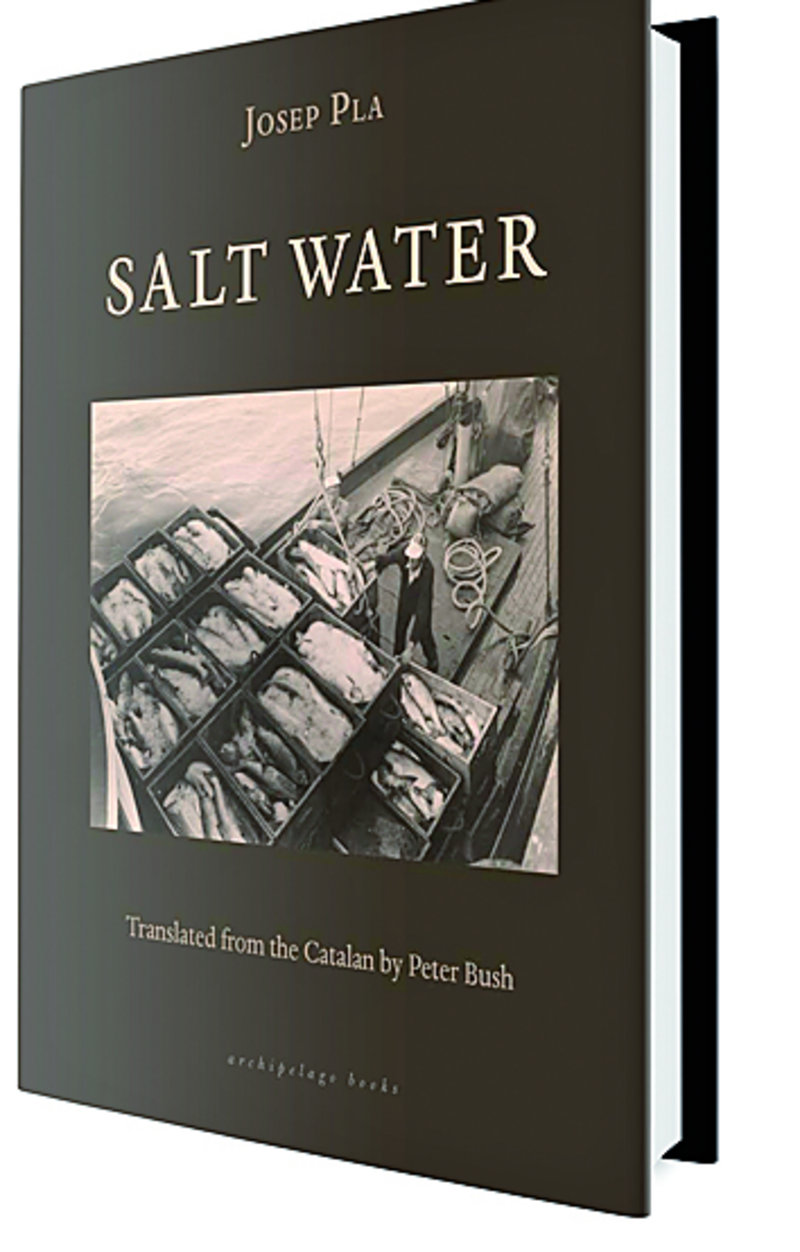

Salt Water is the translation of Pla’s Aigua de Mar, published in his Collected Works in 1966, plus 29 pages on an ill-tempered conversation about a shipwreck with Salvador Dalí’s father

Josep Pla’s introduction concludes that Salt Water “…is something day to day, writing that is insignificant.” Well, he didn’t mean that his writing was not important, but he did mean that it was down-to-earth. “It cannot be placed under the rubric of triumphal, rhetorical, pompous literature,” he insists. Pla was a revolutionary. Not at all a political one, but in literature. He abandoned the pompous style so beloved of 19th-century prelates, politicians and writers. He wrote about his life, the people he met, the things he saw, “something day to day”.

Smugglers and Shipwrecks

Salt Water consists of 10 pieces about life on the sea and in the Catalan coastal villages from Palafrugell to Collioure, focusing mostly on “the aggressively white town of Cadaqués on its silvery-green cushion of olive trees in the depths of the bay” (p.139). The first-person narrator, presumably Pla himself but with the writer’s right to spin a tale, is a terrible gossip, for he listens to everyone and then tells his readers. He travels with smugglers, narrates the stories of storms and shipwrecks that he hears on boats and in cafés and listens to fishermen, bar-tenders, sailors, layabouts, cooks, crooks and eccentrics. You could call most of them eccentric, author included. Pla is proud to comment that the people of his world, the coast of the Empordà, are “a tad unhinged… hard to understand, downright peculiar.”

Pla knows everyone. He hears about Victor Rahola, from one of Cadaqués’ dominant families (Pilar is the most recent), and then he meets him. He bumps into Caterina Albert in the street (p.70) and the two great writers talk about herring gulls (Pla loves to undercut readers’ expectations). He knows Dalí the notary, the painter’s father, and they talk about a famous shipwreck. He hears about Eugeni Ors (“who later converted to Eugeni d’Ors” – a characteristically elegant put-down), then meets him too. Pla is no respecter of the famous, who are spattered only in passing through the chapters. He is more interested in the men (mainly) who live on the sea. Some ride out a storm like Martinet in ’Out to Sea’. Others glide up the coast to North Catalonia with contraband, like Baldiri who survives a northwesterly gale to reach the Salses ponds. The longest piece, ’A Frustrated Voyage’, describes a trip with Hermós, a middle-aged loner searching for the free and footloose life. ’Bread and Grapes’ is both a smuggler’s nickname and the title of a murder story, the chapter of the collection that is most like a classic short story.

These sailing companions of Pla know every cove, current, wind and underwater rock on the coast. They have to: shipwrecks feature in four of the pieces. “The Gulf of Lion,” the sombre Captain Gibert tells Pla, “…is a vessel’s graveyard. It’s an evil place…, a place that has brought a lot of grief to people who have encountered the mistral” (p.351). The mistral comes suddenly on a boat on an apparently calm sea. You have to know how to read the signs quickly or it is already driving you onto the rocks.

Rocks, winds, currents and storms… the sailors brave all these for fish. The book drips with fish, where to find them, how to catch them, how best to cook them. It must have been a fascination and a nightmare to translate (and the translation reads immaculately), for most of the fish and seafaring words are extremely obscure to anyone who does not live on or by the sea. Pla is lyrical on the joys of fishing -- and ironic: catching a fish… “gives the same feeling of uplift that some financial and banking operations produce” (p.304). An entire fifty-page chapter (’Still Life with Fish’) compares the tastes of groupers, hogfish, John Dory, sole, squid, sardines, sea bass, eels and five kinds of red mullet, whose colour he compares to the reds in Velázquez’s portrait of Pope Innocent X (p.283). Pla is both extremely local in his close observation of his coast and a man of wide culture. He bums about in boats with fishermen and enters into learned discussions with the local bigwigs – and some pretty sophisticated ones with fishermen.

Breakfasts at Sea

The book is adorned with detailed tangents on anchovies, language, philosophy or how to build a boat. There is a whole chapter on coral. This might be boring, but Pla’s conversational style is not so rambling as it appears: he makes the coral dissertation interesting by intercalating Greek divers and a lobster lunch. Pla is always eating on boats. He and his friends have incredible cooked breakfasts: wine and a slice of the deep-sea forkbeard “fried and accompanied by a tomato, pepper, onion and escarole salad makes for the loveliest summer breakfast imaginable.” (p.291). Of course, if you wake at dawn and sail for several hours, then forkbeard or two dozen grilled sardines slide down well.

Pla has a special voice, chatting to his reader and confiding in her. Unlike most writers, he uses adjectives for precision. He is a master of colours: “It’s been a gray day: an opaque, pearl-white day, with the sea a wan blue, almost green” (p.69). And he revels in smells. In the barbershop at Sant Pere Pescador, “a dense, dank fug floats in the air: a smell of poor families, cheap perfumes and the effluvia of domestic animals” (p.67).

But do not think he is just a recorder of how things once were. His own voice is always present. Pla expresses opinions, a point of view, often one designed to startle the reader into attentiveness, such as: “Dolphins spoil everything, like too much tomato in a stew” (p.170). With pride, Josep Pla talks in Salt Water of his fierce coast in his and its battered language. He both observes and shares the dreams, traditions, food and culture of its people.

book review

Bitter Life

In the past few years, Josep Pla (1897-1981) has at last entered the English language through his famous The Gray Notebook (El quadern gris), Life Embitters (La vida amarga) and now this book, Salt Water.

Pla is one of Europe’s major 20th-century writers. A liberal journalist in the 1920s and ’30s, he reported from all over the continent for Catalan newspapers. This career was halted in 1936. Pla fled Catalonia: from a family of minor landowners, he was fearful of and hostile to the anarchist revolution. He had connections with the leader of the Catalan right, Francesc Cambó, who supported and financed the military revolt. In exile, Pla spied for Franco on shipping out of Marseille and returned to Catalonia with Franco’s victorious army in January 1939.

Rapidly disappointed by the dictatorship’s anti-Catalan crusade, Pla became an ’internal exile’ at his family’s Mas Llofriu near Palafrugell. During World War II, it is said, he now spied on shipping for the allies. Denied a passport until the mid-50s, he earned a living by writing for the weekly Destino and the press in Castilian. Salt Water suggests he spent much of the 1940s living in several coastal villages, now that he could no longer travel round Europe. Salt Water’s pieces, written in Catalan like all his intimate writing, were first published in the early 1950s, when it began to be possible to publish in Catalan again.