Joan Sales’ lesser known novel:

Winds of the night

Joan Sales wrote only two novels. The translation of his classic Incerta glòria (Uncertain Glory, 1971) was reviewed in Catalonia Today in October 2014. Winds of the Night is the sequel and, though it can be read independently, gains in interest if you have read Incerta glòria first

Inundating the entire novel is the degradation of Catalonia under the dictatorship

Incerta glòria covered the Civil War years through the eyes of three students, Trini, Cruells and Lluís, and their fascination with the brilliant and contradictory Juli Soleràs, one of the great creations in modern fiction.

Winds of the Night (El vent de la nit) is narrated by Cruells. A nineteen year-old student for the priesthood at the outbreak of the Civil War, he is now an impoverished rural priest in post-war Catalonia, his soutane dirty and shiny at the elbows, still obsessed with Soleràs, his “unique friend” with a “lust for life”, and is enticed into occasional meetings with the Falangist provocateur Lamoneda, who seems to know what happened to Soleràs at the end of the war. The four meetings that structure the novel take place in a café soon after the war, in Lamoneda’s sordid flat during the tram boycott of 1951, in Cruells’ village in the early ’60s and in a shack deep in mountain forest in 1968.

Horror of daily life

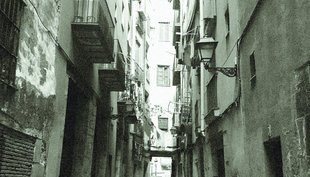

Inundating the entire novel is the degradation of Catalonia under the dictatorship. Here’s Barcelona’s Old City:

“And the river of poverty streamed endlessly by: old women in rags, some drunk, skeletal, bare-legged girls shivering with cold, hunched workers, their toothless mouths sucking on fag-ends they had picked up off the ground.”

Cruells seems to be hallucinating, yet what he sees is real. Surreal vision stems from his hunger and despair; and it is the only way the author can draw close to describing the horror of daily life. The novel transmits the pain of defeat and failure. Cruells fought the war on the Republican side and was interned for several months in a French concentration camp. Returning to Spain and ordained, he is a priest torn apart by his abhorrence of the Church’s support for the dictatorship and has to put up with the general assumption that, as a member of the Church, he supports Franco.

Some of the war’s victors also suffer under the dictatorship. Lamoneda is a fantasist who boasts of his brilliant unpublished novels (better than Stendhal’s), his sexual exploits and his friendship with Himmler. In fact, he is some sort of semi-employed police informer living in a slum. Lamoneda’s long, empty chatter parallels the regime’s official hollow propaganda.

Dark night of the soul

Sales interweaves this powerful portrait of defeated Catalonia with his other main theme: Cruells losing his faith. Unable to ignore the twentieth century’s slaughters, from Kamchatka to Franco to the Nazi camps, Cruells commits the sin of despair.

Cruells abases himself, living for two weeks in hell with a prostitute and her pimp. The wind of the night freezes his neck. Sales is exploring the depths of spiritual anguish, with his Christian character stripping himself of dignity. Cruells escapes with a leap to freedom: poisoning the pimp’s dog and (on Christmas Day) giving away all his money to a beggar. The poisoning and gift are existential, in which Cruells rouses himself from the pit of desiring his death and finds “the iron in my soul” , the strength to resist. Years later he reflects: “The only consolation left to me […], my life wasted, is that I am a loser among the winners.” Consolation because the winners are the tyrants and their lackeys: he has escaped the degradation of being such a winner. He has resisted and can pass on his message to a young, rebellious generation of Catalan priests.

Cruells reflects back on the war, when paradoxically he lived “hours of intense peace”, the only ones in his life, and on Soleràs. For Soleràs betrayed the Republic, crossing to the fascist lines, then in the moment of victory crossed back to the losing side. While with the fascists, he killed the rapist Ibrahim. In Soleràs’ brilliant madness, Cruells finds reason and principle. He contrasts Soleràs with Lluís, who went into exile, made a pot of money, takes a suite in the best hotel when he returns to Barcelona in 1959, yet deceives his wife, Trini. Lluís represents the new Catalan bourgeoisie emerging into the liberalised economy of the 1960s.

Sales’ novel is a political and religious tour de force, written in a ferocious, unrelenting tone. It is both a hallucinatory (though realist) vision of the terrible years of Francoism and a journey through a lifelong dark night of the soul. Hell exists not just in Cruells’ heart, but in the outside world, blown by the wind of the night through a degraded Barcelona.

book review

Neither Black nor red

Joan Sales (1912-1983) was a major defender of Catalan culture under the Franco dictatorship. A law graduate, he fought on the Republican side in the Civil War, first with the anarchist Durruti column in Madrid and later with the Communist 30th Division in Aragon, on the front portrayed in Uncertain Glory. Arrested by the SIM (the Military Investigation Service controlled by the Communists) for not reporting two deserters, Sales was imprisoned in a Stalinist xeca. Released, he experienced the demoralised rearguard, before returning to the front and crossing to France at war’s end.

Sales’ very broad experience of the war assisted him in the writing of Uncertain Glory, which he began on return to Catalonia in 1948 after exile in France and Mexico. The first version was published in 1956, despite the opposition of the censors. Sales obtained a nihil obstat (a “No reason why not”) from the Archbishop. The definitive version, extensively revised, came out in 1971.

A Christian Democrat and Catalan Nationalist, Sales was hostile to both fascism and the left. Winds of the Night contains a ferocious polemic against the anarchist-led 1936 revolution. His fury distorts history. Yet his right-wing but anti-Franco politics make it a rare book about the war. He saw his masterpiece as a payment of a debt to his dead comrades, recording “the truth against the black lie and the red lie.”