Mad times

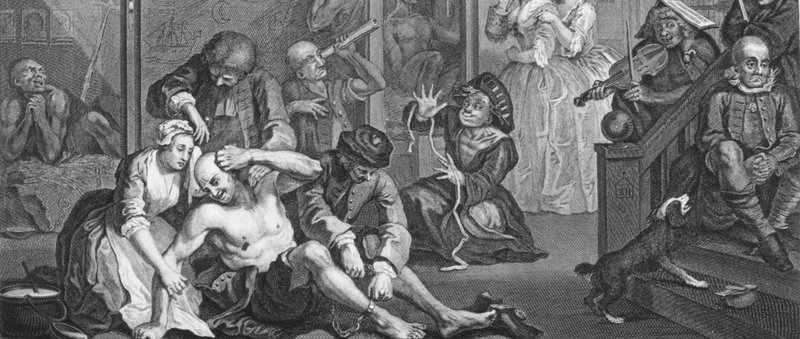

No doubt at all what this novel’s about! From start to end, three friends, the rather dull narrator, the cynical charmer Armengol and the medical student Giberga investigate the eccentric behaviour, then madness, then total mental collapse of their acquaintance Daniel Serrallonga

The Madness is a very straightforwardly structured novel: it covers Serrallonga’s decline in chronological sequence. The friends who analyse Serrallonga (as if he were a lab rat) have three approaches. The nameless narrator is kindly, though ineffective; Armengol is mocking; and the medical student Giberga gives a more distant, scientific view. Then, two kinds of madness are posited: inherited, biological madness and madness caused by difficult circumstances. And Oller implies a third: perhaps the three friends who, unlike Serrallonga, adapt comfortably to a mad world are not so sane, either.

The novel opens in Barcelona in 1867 and focuses on the narrator’s occasional meetings with the wealthy landowner, Serrallonga, and on news and gossip about him over the next 16 years. We learn at the first meeting in a café that Serrallonga, pipe gripped in teeth, eyes that roll back in their sockets when he listens or thinks, shabbily dressed, is eccentric and passionate. He is someone you don’t forget – and the driving-force of the novel is that Oller makes readers want to follow Serrallonga’s story. Haven’t most of us met a Serrallonga – the slightly older bohemian (he is 25; Armengol and the narrator are law students) who overawes us because he seems to have lived more, know more and, so much bolder, care not a jot what people think?

So, who’s mad?

Serrallonga causes a political rumpus in the café and is arrested. While he is in jail. Armengol plays a dirty trick on him, pretending his anti-government articles have been published when they haven’t. The narrator does not like the deceit, but spinelessly goes along with it. The reader next hears of Serrallonga through the medical student Giberga, who describes Serrallonga’s unfortunate family to the two friends in another café. Madness in the family means, Giberga believes, that Serrallonga is “a marked man”, marked by an injury to the brain. He has inherited madness.

This is the notorious ’naturalism’ of the nineteenth-century French writer Émile Zola: that our destinies are preordained by both blood (genes, we would say now) and circumstance, but with no room for personal choice. Zola’s novels sought to show social reality by means of detailed descriptions of places and people seen only from the outside. Though Oller is often cited as the Catalan Zola, this is too facile a label. The Madness contains a lot of psychological insight into the characters’ motives. Nor is Oller writing gloomy novels of predestined failure. Indeed, when Giberga expounds this theory of inherited insanity, Armengol laughingly shouts “What madness! You need to take a long, hard look at yourself.” (p.45) What and who is mad is not always so crystal clear.

Some years later, the narrator visits Serrallonga’s village and meets his crazy sisters. The suicide of Serrallonga’s father and the two sisters’ behaviour are evidence of mental disorder in the family. The narrator learns that Serrallonga has become a member of parliament in Madrid, but does not dare to speak. Then his political hero Prim is assassinated, which plunges Serrallonga into gloom. He takes to his bed for three days, before with obsessive energy insisting to everyone in sight that only he can find Prim’s killers. Everyone agrees he’s been unhinged by Prim’s death. At the same time his sister Adela escapes his control and marries. Then, in furious stubbornness, Serrallonga decides to marry a peasant girl, because it will disinherit his sisters. And so… on to the fateful end.

Shots on the Rambla

Right from the first page, Oller makes readers aware that the friends are living through turbulent times: “There had been shots fired on the Rambla the night before… there were likely to be more that night.” Looked at through the political lens, it is the narrator and Armengol who seem, if not fully mad, at least highly irresponsible, callow and callous. They spend their time lolling about in cafés and playing silly jokes while the queen is overthrown, Prim is killed and the Carlist war rages. Might Serrallonga’s politically impassioned reaction be healthier than this foppish middle-class passivity? To add to this reviewer’s prejudice, the weak-minded narrator then marries in a rather sickly romance “little Matilda.”

Though Serrallonga’s story is what structures the book, it is the social context, the glistening Rambla cafés, the clothes, the conversations between Giberga and the two friends, and the intrusions of political life that make the book so attractive, so realist. The Madness is no dense, nineteenth-century tract. Rather, it’s lively and witty: a tragedy, but written in a light, sometimes comic key.

book review

Pioneering novelist

Narcís Oller (1846-1930) was born in Catalonia’s sourthern city of Valls but he lived most of his life in the capital Barcelona. He worked for many years as a court attorney (procurador): legal details feature in several novels, including The Madness. He translated literature, such as Flaubert, Tolstoy, and Turgenev among others, to Catalan.

Oller was the first great novelist in Catalan since Joanot Martorell 400 years earlier. While his contemporaries Àngel Guimerà (born 1845) and Jacint Verdaguer (born 1845) were leaders of the Catalan literary resurgence in theatre and poetry, respectively, Oller was the leading novelist. All three belonged to a generation that was consciously remaking Catalan as a literary language.

In fact, Oller started writing romantic novels in Spanish, but switched in 1877 to Catalan. Until his generation, Catalan speakers tended to write in Spanish. It was the example and success of Verdaguer that persuaded Oller, against the advice of Spain’s preeminent novelist Pérez Galdós, to switch to Catalan. Galdós considered Catalan a naive, uncultured language. It was “absurd” to write novels in Catalan, as novels require “extremely rich and flexible diction.” With admirable forbearance, Oller responded that Catalan was his language and it would be “false and ridiculous” to write in another. “Don’t you think that language concretises the spirit?” he asked Galdós.

His first major novel La papallona (The Butterfly, 1882) described an orphan girl’s struggles. The 1885 introduction by Zola to the French translation led critics to place Oller firmly in the naturalist tradition, despite La papallona being more romantic than naturalist. Oller shares with Zola the fatal decline of his main character. He shares too the detailed observation of people’s conduct and circumstances that is characteristic of naturalism, but Oller is more humorous, more optimistic and looks more at the emotions and motives of his characters. Really, he was only in part a ’naturalist’ writer.

La papallona was followed by L’escanyapobres, The Moneylender (1884), about two misers whose passion for money destroys them; then Vilaniu, the name he gave to his native Valls, in 1885. His most famous novel La febre d’or, Gold fever (1892), tackles the money-lust and speculation of the newly rich bourgeoisie in the 1870s.

Oller wrote theatre and many short stories, but his last major novel was the stylistically sophisticated and psychological Pilar Prim (1906), a study of a young widow’s struggles to survive her family’s greed and suitors’ attentions.