1992

1992 was a watershed year in Spain. After 15 years of reforms (democratic transition, European integration, a modern welfare state…), the New Spain celebrated its transformation through four – yes, four! – simultaneous events: the Seville International Exposition, the Madrid-Seville high-speed railway opening, Madrid’s hosting the European Capital of Culture and Barcelona’s Olympic Games. Yet these four events portrayed modern Spain in more ways than intended. Seville’s Expo became a byword for waste, incompetence and corruption that left little behind except debt. The Madrid-Seville high-speed train has produced nothing but losses. Madrid’s cultural opportunity was spent and quickly forgotten... Then, as soon as the fiesta was over, came the day of reckoning: international markets started to bet against Spain’s increasingly uncompetitive economy and, as a result, the peseta devalued three times in the year after the Olympics closing ceremony.

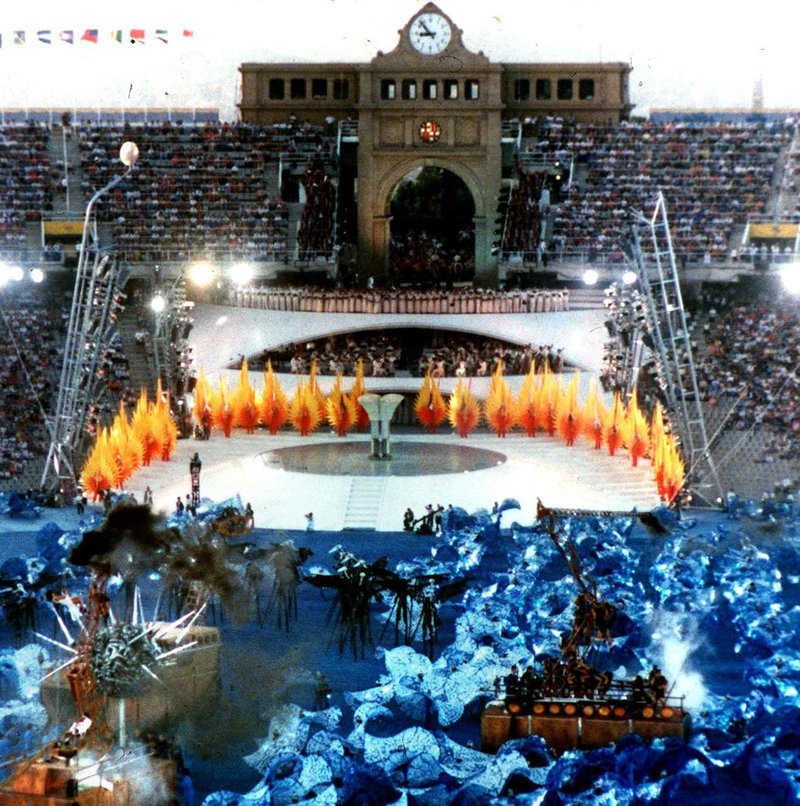

Yet the most powerful symbol was, without doubt, Barcelona’s Olympics – only it was a symbol of something very different. The event is remembered even today as one of the best-organised Olympics in history, a resounding success that launched Barcelona as a global capital of tourism and, perhaps most importantly, a triumph of Catalan civil society through thousands of young volunteers who gave up their summer holiday to work for free – something you would not find at the Seville and Madrid events. It was a resurrection. In the 1980s, as Spain removed its industry’s tariff protection as part of its European integration programme while keeping interest rates at up to 16% to prevent devaluation, Catalonia, formerly “Spain’s factory”, fell into a deep decline from which it was difficult to believe it would ever emerge. Meanwhile, Spain’s government spending climbed during the 1980s from 20% to 45% of GDP, which allowed it to siphon more resources than ever before to other regions… while inflicting on Catalonia’s economy what Ramon Trias Fargas described in 1985 as a “premeditated asphyxiation”. Yet, somehow, the Catalan economy reinvented itself and, in 1992, its capital earned the world’s admiration as a centre of modernity and style. If imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, in the subsequent decades Barcelona (and thus Catalonia) received praise from the entire world – including Madrid, Valencia, Lisbon…

Hence 1992 marked the start of a new escalation in Spain’s secular conflict with Catalonia – the hard-working, entrepreneurial, always-rebellious Eastern region. Making concessions to Catalonia (such as autonomous governance or the Olympics) was politically easier in the 70s-80s, when the Catalan economy languished in decline while Madrid rose to become the third largest metropolis in Western Europe. Barcelona’s astounding success in 1992, heralding Catalonia’s new global projection while emphasising the potential of the Mediterranean coast, triggered the opposite reaction – for, in the long run, economic power shifts often precede political ones. Thus, recentralisation pressure and that old “premeditated asphyxiation” became much stronger from the mid-90s on. Which, naturally, elicited a response, first in a new Statute of Autonomy to protect Catalonia from this state-sponsored discrimination and, when this failed, a growing popular claim for political independence.

Paraphrasing Thucydides, the Athenian historian, we might say it was the ascent of Catalonia and the fear it instilled in Madrid’s establishment that made the conflict inevitable. This is why neither the Catalan claim for independence nor the State’s shameless repression show any signs of abating – for, against the hopes of European observers and middle-of-the-road Spanish journalists, both sides realise the conflict can only end when either the State manages to clip Catalonia’s wings so short it can never soar again or, else, Catalonia frees itself from the clutches of that State.