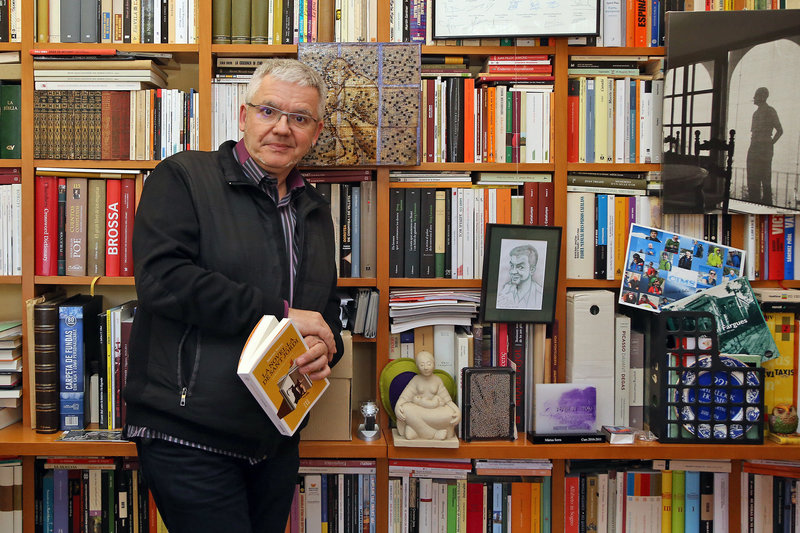

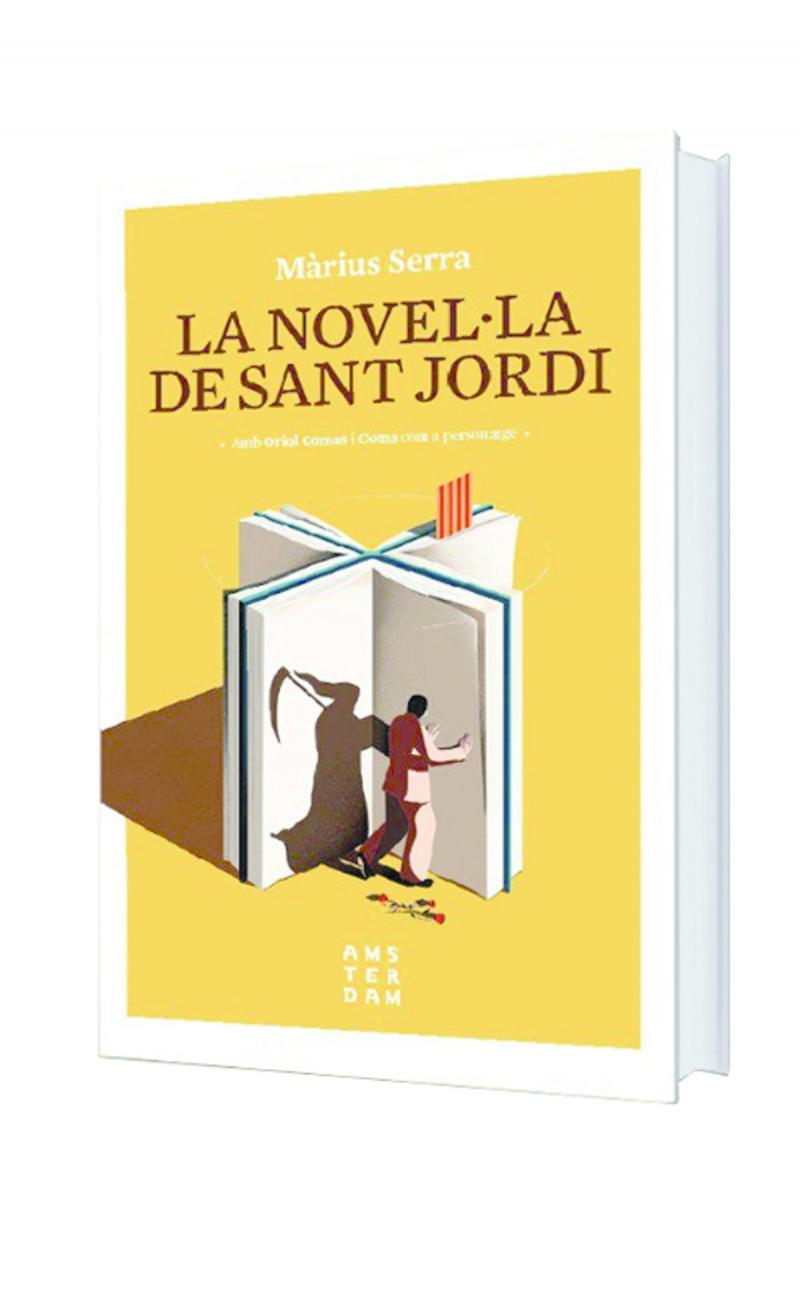

La novel·la de Sant Jordi is your first noir book, a parody of one of the most popular local celebrations, with direct references to real life people from the publishing industry, institutions, the media... How do you expect them to react or feel after reading your book?

I have no expectations. I assume some people will dislike it, but my main aim in writing this novel was to drive a noir vehicle and invite the reader to get in the car and have a nice trip. There is crime and humour. Of course, there are also some sharp contradictions related to the attitudes of publishers, journalists and authors. Sant Jordi is almost a hundred years old and has grown so much that it is now overwhelming. It is a mass cultural experience based on a very minority activity: reading. Sant Jordi’s Day is now like a Champions League Final, with international authors coming from all over. They must think we Catalans are great readers, but this is just once in a year.

The book is set in the new Catalan Republic and Màrius Serra is the protagonist: a book within a book. How did you come up with the idea of this novel of a different Sant Jordi?

My first Sant Jordi as a writer was in 1988, long ago. When I was a completely unknown author, people used to ask me for other authors’ books, because they saw me standing there and thought I was a bookseller. Many times, in the middle of a messy Sant Jordi, I have thought: “I have to write a novel about this, and kill someone!” When, in 2001, Javier Cercas published “Soldiers of Salamis”, he started, even without realising it, a sort of 'selfie' literature movement. Auto-fiction has spread in this century as a real plague based on a drug called Ego. To make an effective parody of this selfie literature I was obliged to put myself (and my self) in the novel. Commercial books and literary auto-fiction were two of the first ideas for me to start writing La novel·la de Sant Jordi.

For the main character, Màrius Serra, it is his first crime novel...for the real Màrius Serra as well. What were the main challenges you faced when taking on noir literature ?

I am an omnivorous reader, but in the last decade I have read many noir books, and quite diverse ones, by Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, Andrea Camilleri, Petros Márkaris, Henning Mankell, Jo Nesbo, Pierre Lemaitre, Fred Vargas, Andreu Martín, Benjamin Black, Michael Connelly, Ferran Torrent... I have a humble attitude towards the genre, because I think it has very strict rules. My approach is playful. I try to introduce games into the story, with a main character based on my friend Oriol Comas i Coma, who is in real life a prestigious expert on games. A crime novel needs rhythm, clues to speculate on, facts and fiction... It has been a great experience to open a door like this.

Any similarities between the Màrius in fiction and the real one? Is self-criticism necessary to be able to criticise others as well?

The fictional Màrius is very similar to me, but I have deformed him through parody. To write parody about all the components of the literary world I had to start with me. I believe critical thinking is fundamental to avoid fanaticism, so self-criticism is not just strategic in this novel.

You use black humour and an ironic tone to talk about one of the most loved Catalan celebrations. What is living Sant Jordi like from the inside?

Sant Jordi is an exciting day. Booksellers, publishers, journalists, authors and everybody gets involved. This is a massive event throughout all Catalonia with a special focus in the centre of Barcelona. Millions of people celebrate it. Humour is a good filter for approaching complex situations. Love is in the air, theoretically, because lovers buy books and roses as gifts, but there are more feelings in the air: envy, jealousy, even rage. Finally, thousands of people work hard for weeks to flood the streets with books and roses.

Why did you choose the mystery, crime novel genre to talk about Sant Jordi from the inside?

I thought it would be a good way to show some of the contradictions between art and commerce, about literature and books, so to speak. In a sense, I built the novel like I do when I create a crossword. The very first sentence of the novel talks about a sleeping killer, and afterwards I show six male characters who could be the real killer: a journalist, a publisher, a businessman related to books, someone related to the university, a games creator and a writer called Màrius Serra. It resembles a logical enigma, with crimes announced before they occur.

How did you get to Oriol Comas for the main character?

We have been friends since the eighties. We both love playing games, in my case based on language, mainly. Ten years ago we started creating some board games and in 2015 I made this strange proposal: would you mind being a character in a novel? Of course, we established some conditions. He is coauthor of the novel, but I write everything. He reads, we discuss it, and I can ask my own character how he would react to so and so. Writing a novel is an intense experience but an isolating one, too. It has been great to share such a solitary activity with a good friend.

Is this the first novel in a series with Oriol Comas as the protagonist?

Yes, that’s the aim. We have already started work on a second one, and my intention is to write a couple more.

You also said that this is a novel written with two hands but two brains, together with Oriol Comas...what about the writing process for this book?

We are both authors but there are only two hands on the text. I am uniquely responsible for the writing itself. He is the main character, and it’s great to have him at hand. He is a character in real life. He is very creative, singular and playful, so it’s always fun to meet him. When you create a fictional character you have to think very much about the personality you will give him or her. In this case, it’s easy. I just call him to have a drink and ask.

You said that you have been preparing to write this novel for 30 years. How has Sant Jordi evolved since 1988, the first time you participated as an author?

It used to be a civic event, related to Catalanism and literature. In fact, it has a commercial origin. The first Sant Jordi was held in 1926, created by a publisher called Vicente Clavel. In the 1960s and 1970s new publishers started to publish more and more books in Catalan, so it became a day to sort of promote the culture. That’s what Sant Jordi was when I started to read and since then it has grown a great deal. In Barcelona, booksellers just used to be on the Rambla, from plaça Catalunya to the sea, but very soon Sant Jordi colonised Rambla Catalunya and Passeig de Gràcia, apart from the other places in town and all the other Catalan cities. This growth caused Spanish and international authors to start coming. Nowadays it’s a sort of literary Oktoberfest in April.

Does Sant Jordi really promote reading or is it just an opportunity for booksellers and publishers to boost sales?

Reading is a very quiet activity and Sant Jordi is noisy. Of course, if you are surrounded by books it’s easy to start reading, but a big fair is definitely about sales. Leonard Cohen sang “First we take Manhattan, then we take Berlin”. Sant Jordi is just Manhattan. Maybe we will read at Berlin.

Do you think Sant Jordi’s Day has grown too much – is it becoming a victim of its own success?

In my opinion, the evolution of Sant Jordi’s Day obeys the logic of all commercial campaigns. Nobody wants to admit they have sold too much. There is a constant debate on Sant Jordi, but the fact is that today nobody would be able to create something like this. I love Sant Jordi. My novel is a declaration of love, but I don’t think it’s a good idea to concentrate all efforts on a single day. Everybody in the publishing industry knows that, and they try to extend the visibility of books to other periods. Sant Jordi is not going to be a victim of its own success, but literary publishing could be a victim of Sant Jordi. Dragons are literary books.

This is the first time you have published with Amsterdam, and there is no page 155...

I work book by book. I mean, I have never signed a contract for three or more books, as some publishing houses offer. I have published with Pòrtic, Columna, Empúries, Proa... all of them absorbed by Grup 62 and, afterwards, by Grupo Planeta. I had the feeling that this novel had to be published in another environment, and I must say that I am very happy to now be with Amsterdam. I feel comfortable with this humble protest against the ignominious application of 155 by the Spanish government.

English language and culture are very important for you. Why did you decide to study English philology?

I decided to get into the English language and culture because of contemporary music, mainly. I used to play keyboards in some music groups in my adolescence. All my cultural landmarks were in English, even as a reader. I was shocked after reading Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man and, after a lost year trying to study medicine with no vocation for it, I rectified and studied English Philology at Barcelona University.

You are passionate about languages and literature and reading, you are a prolific writer, you do crosswords, puzzles, plays on words... how do you find the time and energy for all that?

Because I feel it’s a privilege to do what you love, even for a living. Of course, I work hard, but my fuel is passion. Passion for language and literature, passion for life. I feel I could be an antonym to Bartleby’s “I’m not in the mood”. I try to always be in the mood. Life can be short: Ars longa, vita brevis.

What are your plans and projects for the near future?

Just to keep on playing, reading and writing while I live every day with my beloved (which in English sounds very bombastic, but is precise) and friends. From the creative point of view, I would like to write a few more noir novels with Oriol Comas i Coma, and hopefully in 2019 my drama version of my book “Quiet”, titled “Qui ets”, will be on stage.

What are your favourite books and writers (dictionaries included)!

I always find it difficult to establish a list, because it depends on time. I am very promiscuous with authors. Today I would say Joyce, Cortázar, Rodoreda, Perec, Sterne, Zweig, but tomorrow I could say other names. My favourite dictionary is Joan Corominas’ Diccionari etimològic i complementari de la llengua catalana. It’s the greatest novel ever written in Catalan, and every single word of our language is a character.

How do you feel new technology is influencing writing and literature in general?

I have never thought new technology would be an enemy, but it is true that social networks reduce reading habits. From the creative point of view, the digital era has changed the world, so it has a deep influence. I still think that the Internet is a place where minorities can meet and play new roles. When I was an adolescent we made fanzines and tried to spread them around our neighbourhood. Today it’s possible to deliver them all over, even generating nodal communities, with a different sense of hierarchy. But there is too much noise, too much intoxicating news, too much pollution.

interview

interview màrius serra