books

daniel pALOMERAS. GP and writer

Charles Bovary 'Officier de Santé'

The fracture was a simple one, without any kind of complication. Charles could not have hoped for an easier case.Then calling to mine the devices of his masters at the bedsides of patients, he comforted the sufferer with all sorts of kindly remarks

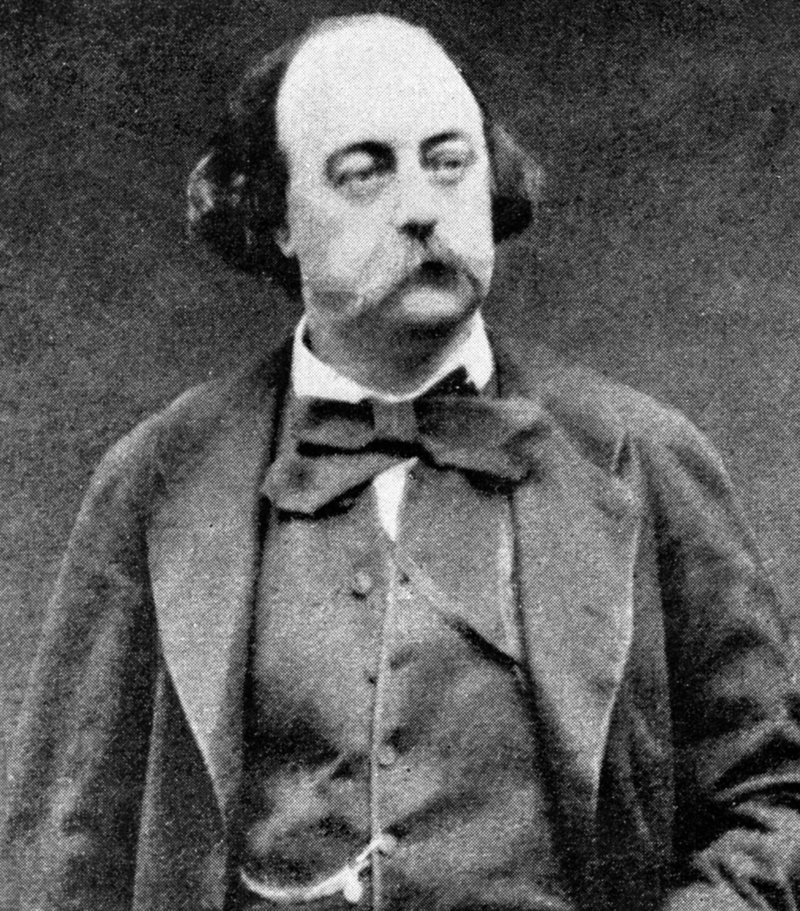

£Strictly-speaking, madame Bovary’s husband was not a doctor, although M. Homais, the apothecary of Yonville, flatters him as such. No, Charles was a humble officier de santé (health officer). In the 19th century, French medicine was split into a dual hierarchy that reflected the division between the bourgeoisie and the commoners. The officier de santé was a doctor of a lower order, who had studied medicine without passing the final examinations, and who could only practice in a limited way in the département (administrative region) in which he had qualified. They were semi-doctors who were not allowed to perform important surgery without the supervision of a real doctor. This fact will be relevant in the professional biography of M. Bovary. Gustave Flaubert knew these circumstances well, as his father and brother were prestigious surgeons in Rouen. On the two occasions in which he shows us Charles Bovary in situations that exceed his professional limitations, he has to resort to celebrated doctors from the capital. The latter is when he discovers his wife, Emma, has poisoned herself with arsenic.

Charles was far from being a brilliant student: “ridiculus sum” (I am ridiculous, in Latin) was the line he was forced to copy out over and again by his teacher on his first day of school. At the medical faculty, he showed he had a good memory, but he understood nothing. Yet, that was not to the detriment of his vocation or his good intentions. He was captivated by Emma’s eyes, eyes that would later captivate other men: “dark eyes that seemed black”, “black in the shade and dark blue in the daylight”. In Flaubert’s Parrot, Julian Barnes scolds the critics who take the wonderful novelist to task for changing the colour of his heroin’s eyes from brown, to blue or black. In truth, what is the importance of such a trifling detail? Once married, Charles’ work was tough: “Charles in snow and rain trotted across country. He ate omelettes on farmhouse tables, poked his arm into damp beds, received the tepid spurt of blood-lettings in his face, listened to death-rattles, examined basins, turned over a good deal of dirty linen.” Charles limited himself to prescribing sedatives, occasional emetics, footbaths, or leeches. And, it must be said, he worked with dirty finger nails and a three-day beard. He received a phrenology bust as a gift to decorate his surgery, but he was not a real doctor.

And here we come to his great failure at surgery that fed his greatest fears. It was an error that came from an excess of ambition that superceded his knowledge. It is the operation on Hippolyte, the crippled servant at the inn in Yonville. Under pressure from Emma and Homais, Charles attempts to operate on Hippolyte’s club foot. The author tells us that not even the great Ambroise Paré tying up an artery for the first time, or the eminent Guillaume Dupuytren’s first treatment of a brain abscess were as nervous as Charles Bovary with the scalpel in his hand.

The operation is a disaster, the wound becomes gangrenous and Hippolyte has his foot amputated by Dr Canivet from Neufchâtel, who is scornful but efficient. Emma gifts the servant a false leg, but thereafter a remorseful Charles avoids Hippolyte. The sad medical biography of M. Bovary is narrated in Flaubert’s precise, well-worked style, which avoids flamboyance that might detract from reality, with no concessions to opinion or personal experience, say the experts. With an exception, I’d say: the recognition of his doctor father and brother. While veiled, the novelist pays tribute to them in the figure of Dr. Larivière, who appears during Emma’s final moments: “the apparition of god could not have caused more excitement.” This physician is from M. F. Xavier Bichat’s great school of surgery: “that generation, now disappeared, of philosophical practitioners who, cherishing their art with a fanatical love, exercised it with a passion and wisdom!...Scorning medals, titles and academies –hospitable, generous, fatherly with the poor and practising virtue without believing in it... His gaze, more incisive than his scalpels, would penetrate right into your soul, right through every pretension and every reticence, and excise every lie hiding beneath.” It is the lesson of medicine hidden in the tragic pages of Madame Bovary.

*