China and the new global geopolitics

China has become an economic force in today’s global market and must now be considered the second great world power in this respect

The visit to Taipei by US Democratic Congressional Leader Nancy Pelosi sparked tensions between Beijing and Washington

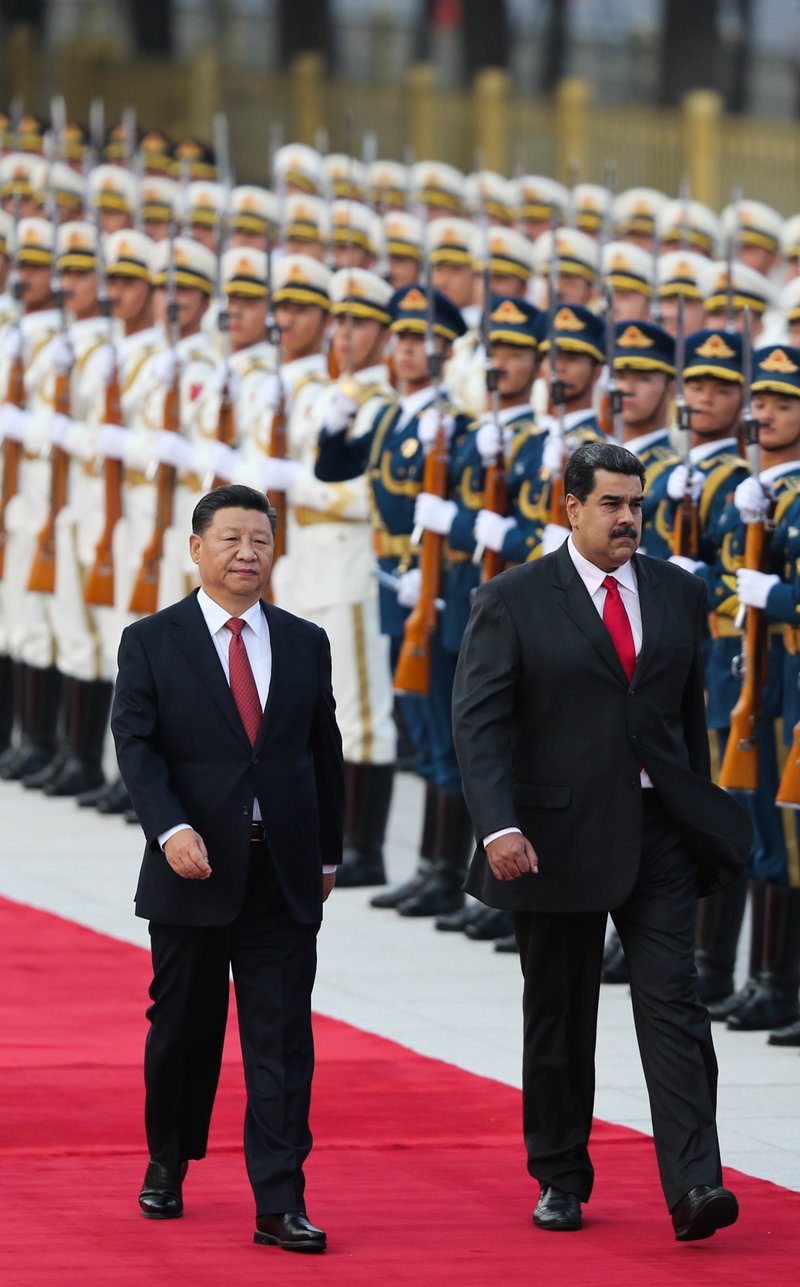

Xi has remained loyal to Deng’s model, projecting China’s economic, commercial and financial power around the world

The People’s Republic of China is the most populous country on Earth and accounts fro around 18% of the world’s population. It is also the largest economy (according to GDP based on purchasing power parity), ahead of the United States, India, Germany and Japan, although in terms of GDP per capita (16,400 dollars in 2020), which is a better measure of standard of living, it falls to 102nd place, far behind most European countries. However, it has become the world’s leading exporter in recent years, ahead of the United States, Germany, Japan, France and the United Kingdom, and the second largest importer in the world, behind only the United States and ahead of Germany, France, Japan and the United Kingdom.

The situation contrasts with – or is the result of, depending on how you look at it – the fiasco of the Great Leap Forward (1958-1962) and the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), the latter resulting in a deep economic stagnation and the deaths of millions of people, and forcing a profound modification of economic guidelines following the death of Mao Zedong (1978). Change came in the form of Deng Xiaoping (1978-1997), who had survived the purges and, to Washington’s satisfaction, promoted the creation of “special economic zones” that enjoyed greater freedom of trade with foreign countries, importing Western technology and foreign investment, while strengthening the pre-eminence and leading role of the Chinese Communist Party. Over 10 years, China’s GDP doubled and the economy grew at an annual rate of between 9% and 11%. These were the foundations of today’s economic power, despite post-Covid-19 challenges. Deng believed that two economic systems could coexist under a single political system. It is the same principle, “one country, two systems”, that it applied in order to achieve the reincorporation of Taiwan and to agree with Margaret Thatcher on the transfer of sovereignty from Hong Kong.

Since the beginning of the second decade of this century, Xi Jinping has held maximum power in the country (President of the Republic and Secretary General of the Communist Party) and will be able to do so for more than two terms because, in accordance with the 2018 constitutional amendment that abolished the limitation, this was approved at the party’s 20th Congress on October 16. Xi has remained loyal to Deng’s model and expanded it, projecting China’s economic, commercial and financial power around the world. At the same time, he contests North American hegemony and the institutions of economic and political governance arising from the Bretton Woods Conference, objectives he shares with Vladimir Putin’s Russia. However, Chinese diplomacy is more sophisticated and less aggressive: in the South China Sea, it is pushing the mechanisms of hybrid warfare – including military manoeuvres, occupations of archipelagos and the creation of artificial islets – to keep the conflict dormant, while all the time on the verge of war. Beijing’s attitude towards Taiwan is very different, however, as it considers this a matter of domestic policy. The island was the last stronghold of the nationalist troops of Chiang Kai-shek’s Kuomintang party, and the only option envisaged by the Communist Party, which has never recognised Taiwan’s independence, is reunification. This summer’s visit to Taipei by US Democratic Congressional Leader Nancy Pelosi sparked tensions in relations between Beijing and Washington and military manoeuvres by the two powers in the region.

Beijing’s strategy initially depends on financing the consolidation of BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa) and its majority contribution to the creation of the New Bank of Development (NBD, based in Shanghai) in 2013, which exists outside the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. Argentina, Iran, Egypt, Saudi Arabia and Turkey have shown interest in joining the BRICS. Through the promotion of greater cooperation on economics, politics, military and international security, Beijing also aims to transform the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO), which includes China, Russia, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, India, Pakistan and Iran, and proposes the creation of a single currency for the group to become a “concert of great non-Western powers”.

In 2013, Ji Jinping announced the Silk Road Economic Belt (SREB) project, which promotes connectivity between participating countries and encourages Chinese investments to build infrastructure, often related to the extraction of hydrocarbons and minerals, without excessive sensitivity to environmental standards, and which at the local, state level often results in corruption and indebtedness. Earlier this year, it presented a new strategic framework, the Global Security Initiative, to foster bilateral and multilateral relations with the Global South (Southeast Asia, Africa and Latin America), which is where the main Chinese investments are concentrated.

China’s strategy depends on weaving a network of alliances broad enough to develop parallel global governance and confront, if necessary, any possible sanctions from the West. Along these lines, it is worth noting the strengthening of bilateral relations with Saudi Arabia, Venezuela, Iran and Pakistan. In this context, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has been an inconvenience, as Indian prime minister Narendra Modi, and, more discreetly, Ji let Putin know at last month’s SCO summit in Samarkand. This highlights the asymmetry of relations between Moscow and Beijing, despite the “pro-Russian neutrality” exhibited since last February. China has provided Russia with economic support, while taking advantage of falling prices of Russian gas and oil with falling Western demand. In short, as Alexander Gabuev (Foreign Affairs, August 2022) pointed out, unlike seven decades ago, when Mao went to Moscow to visit Stalin, China today has a more robust and dynamic economy, and better technological and more global political and economic influence than Russia. This asymmetry will be even more pronounced in the coming years, since Putin’s regime depends on Beijing for its survival.

feature international