Where punk meets art

Despite no direct connection, the radical and rebellious nature of punk can be seen in the artistic output of the time

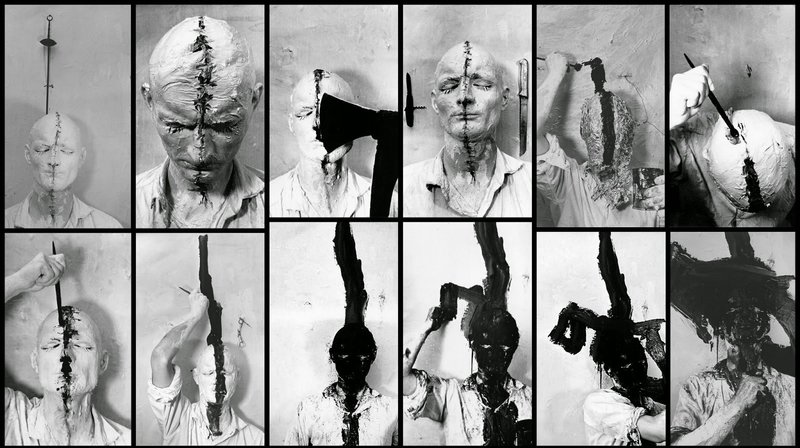

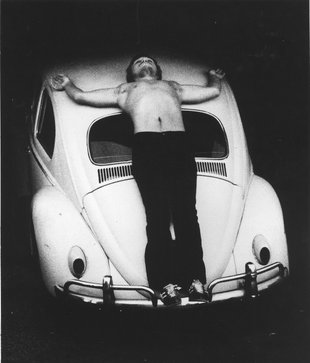

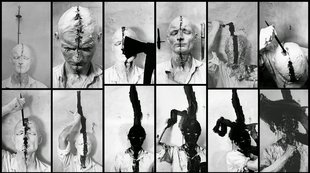

Dissatisfaction has always driven artists to do new things. Jordi Benito put his life in danger to exorcise anxieties about the oppression of the individual by convention. His corporeal “performances” were nauseating. In 1979, he sacrificed a cow at the Miró Foundation and hung it upside down and almost suffocated rolling in its blood. A year earlier, he had tried something similar with a human corpse at the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris.

The radical nature of this unique artist coincided with the upsurge of punk. Initially without any direct connection, there were nevertheless the same undercurrents. In fact, the art world was ready for the impact of punk and its need to undermine bourgeois values.

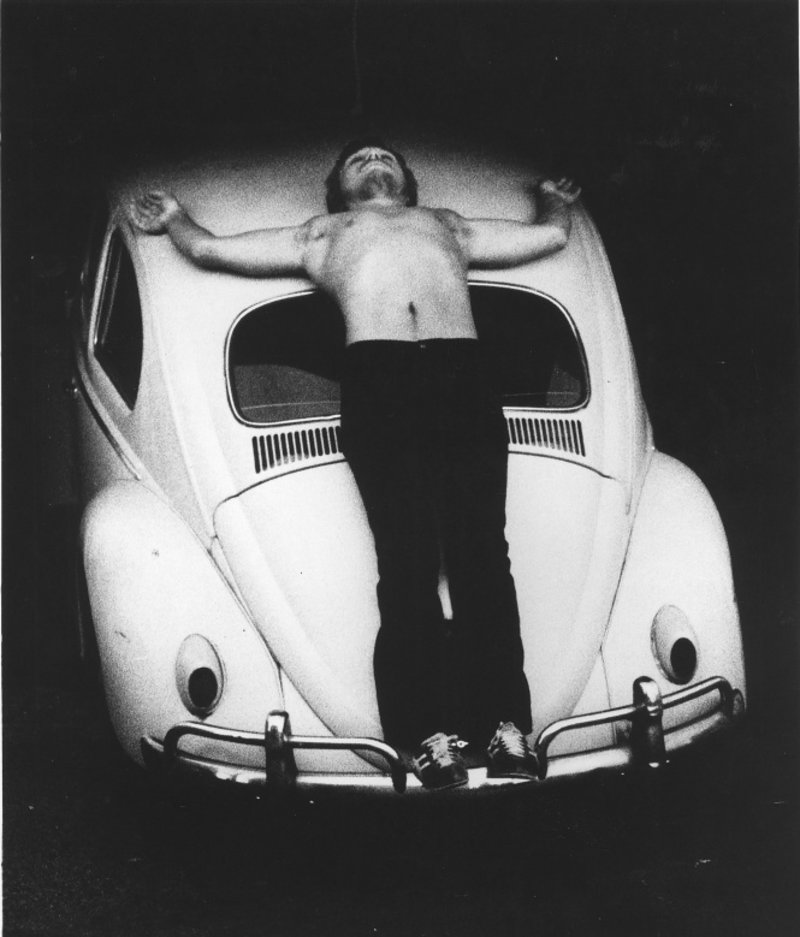

More visionaries emerged rebelling against the commercialism of art, such as Vito Acconci, biting his body and masturbating in public; Francesc Torres, looking for his atavistic self in drunkeness; Chris Burden, flirting with death. Burden died suddenly in 2015, but had time to meet the request of curator David G. Torres and design an exhibition on the influence of punk in contemporary art. Punk. Els seus rastres en l'art contemporani (Punk. Its traces in contemporary Art) opened in Madrid, went to Vitoria, and was in Barcelona last year. The fans were thrilled: it was the second most visited exhibition in the MACBA programme. It is now in Mexico.

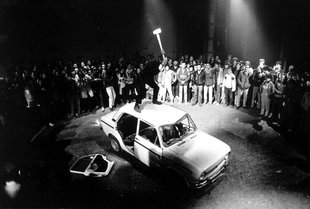

Torres says he did not go looking for artists with any sort of “punkability”, but rather artists who infected him with their extreme and revolutionary impulses. More than influence, he prefers to speak of a collective mood: “What I wanted to show was the intensity of this period in 1977 and how it spread in contemporary creation and, in particular, art. The willingness to challenge yourself and be challenged constantly is the origin of punk and so it is normal to find a resonance in art because it has, throughout the 20th century, been the space most open to questioning,” he explains.

“Punk was the answer to moments of an intense avant-garde. The CBGB concert centre in New York was the '70s version of Zurich's Cabaret Voltaire [the dadaist Mecca] and the London shop Sex London was key in many spontaneous happenings,” with a group formed in 1957, anticapitalist to the bone, which understood art as the only means of social transformation. There were even more surprising connections: “On the covers of some of the iconic punk groups like Fugazi, there are references to Russian Constructivism and Bauhaus, which in principle had nothing to do with punk.”

Invisible threads connected these moments of creative exaltation. Dada was punk and punk was Dada. Dadaist muse Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven walked the streets of New York with coffee spoon earrings, postage stamps on her cheeks, a shaved head streaked with colours, a funeral wreath on her head and her lips painted black.

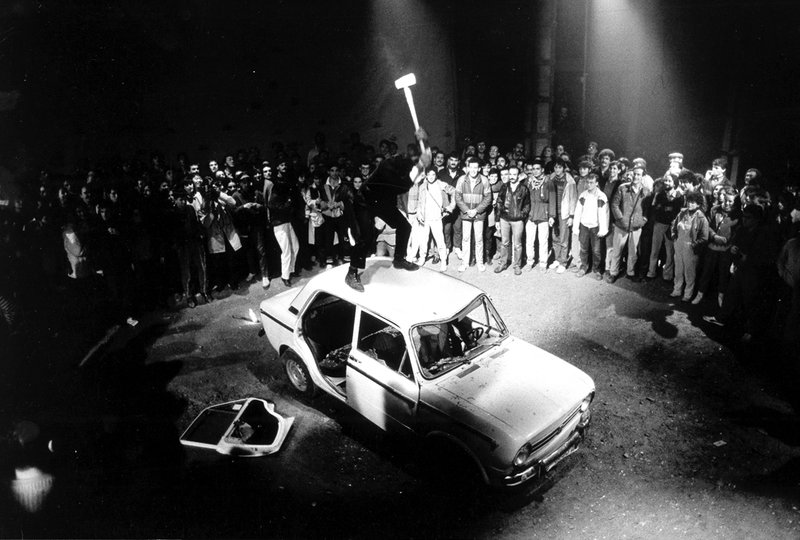

With this background noise, the punk incursion provided artists with new stimuli to express discontent. “In Catalonia, many artists in the '80s picked up the torch. Despite their academic background, Mabel Palacín, Jordi Colomer, Tres or Marcel·lí Antúnez fed off the concerts of the Sex Pistols, Sonic Youth or La Banda Trapera del Río. We have an unfortunate tendency to compartmentalise what really is in the same box. It was a cauldron of shared thought,” says Torres. The punk spirit intertwined with Viennese Actionism took Fura dels Baus to the vanguard of a new language. Their shows went to extremes, with destruction as freedom. “With Fura, punk acted as a catalyst and gave a breadth to global spectacles that were ours: the cercavila, the slaughtering of the pig, trabucaires ...,” says Torres.

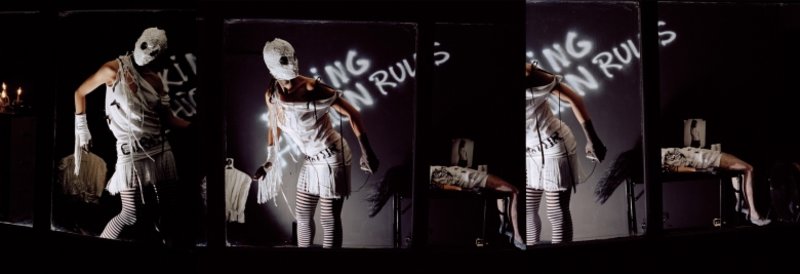

What followed was even grander. In the '90s appeared another batch of artists imbued with the same ethics and aesthetics but sophisticated, like Joan Morey. “Morey brought us the alienated condition of the individual in society, the crisis of modernity, the darkness, ...” in a regeneration of performance that provides a new and unique critique on the issues of gender and sexuality.

Traces of punk art survive. There are projects like Nuria Güell's that challenge the system or Victor Jaenada's nihilistic installations. And on another level, Damien Hirst and his sharks in formaldehyde and human skulls encrusted with diamonds. Torres argues: “When Hirst says he is a punk artist he is quite aware of what he is saying. The Sex Pistols reappeared in 1996 for the Filthy Lucre Tour. Just that, cash in and clean up. Cashing in on things, which Duchamp also did, is a perfect punk attitude. And Hirst goes there: the best way to go against the system is to bring it to paroxysm. The idea of punk as fraud dates back to its origin: it was said that it was a marketing strategy to get rid of surplus leather and chains.”

Punk on the page

Punk also made itself felt in publishing, notably with Salvador Costa Valls' book, Punk. The volume of Costa's photographs was published by the Barcelona magazine, Star, in 1977. An expert photographer, Costa visited London to witness the new cultural movement with his wife, Montse Ferré: “We were there for less than a week but Salvador took a thousand photos. The idea was to sell the photos to the Star magazine, but with so much material Juanjo Fernández and he decided to do a book,” she says. The photos provide unique testimony to the fleeting punk movement that would go down in cultural history. / D.C.