A wild beast filled with colour

This sumptuous large-format book of some 300 colour and black-and-white paintings, drawings and photos tells the story of Carles Nadal's life and his colourful and happy art

Carlos, or Carles, Nadal was dubbed the heir of Dufy and Matisse, 'the Last of the Fauves'. Matisse and André Derain were called Fauves (Wild Beasts) on exhibiting in Paris after a long stay in 1905 painting in Cotlliure (Collioure) in French Catalonia. Their main features were a heightened use of colour and daring shapes: they gave new possibilities to colour.

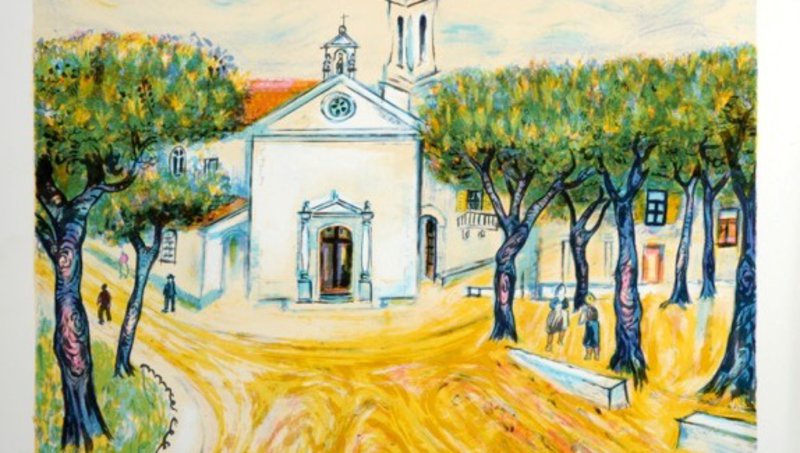

And Nadal indeed used colour. “First he laid down a base of colour and then drew on top of it,” his son Alexandre Nadal explained in a 2012 interview. The cover to this book shows a painting Nadal did on a trip to Cuenca in 1978. A whirling group of trees in blue surrounds a carpet of red grass and a dash of yellow cornfield on one side. Houses sit still in black and white ink austerely behind the trees and above the town black and white clouds of a storm scud over the sky. The leaves of the blue trees look like the dresses of whirling dancers; the trunks, their legs. There is no detailed realism here, but an expressionist interpretation of nature. Both sky and blue trees move with the tension of the coming storm, in contrast with the simple lines of the town.

Many of the ink and wash drawings on paper included in this book were sketched in the open air. But Alexandre maintained that his father was basically a studio painter:

“Josep Amat was my father's landscape teacher and they enjoyed a long and close friendship. So it is said that my father was a landscape artist, but I think not. He painted in his studio. He went out walking and took notes, such as red car or blue roof... then he went to the studio and started painting.”

Nadal was heir to both Catalan and French traditions of art. Close friend of Braque, admirer of Les Fauves, yet he learned his craft in the Catalan school of landscape painting. When he returned to Catalonia, it was to Sitges, home in the 19th century to seascape painters who enjoyed its special light (not dissimilar to Cotlliure's) and then to Catalan impressionists such as Santiago Rusiñol.

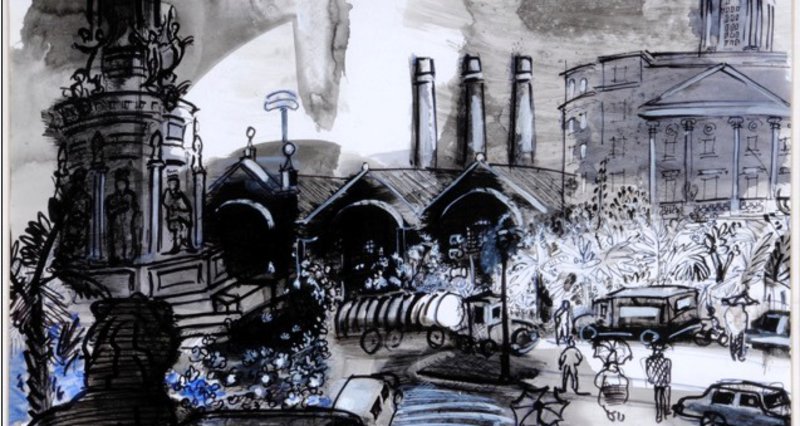

Works on Paper is divided into sections. The first 'Cities Towns and Villages' takes up half the book and has drawings and paintings (the distinction is not real or useful, as each Nadal work is both drawing –its lines visible– and painting) from Barcelona, Sitges, Paris, Cuenca, Moscow, Manchester, among other places –Nadal was a great traveller. The work is interspersed with photos of views drawn by Nadal and of the artist. Many of the works are outdoor sketches in ink for oils done later in the studio.

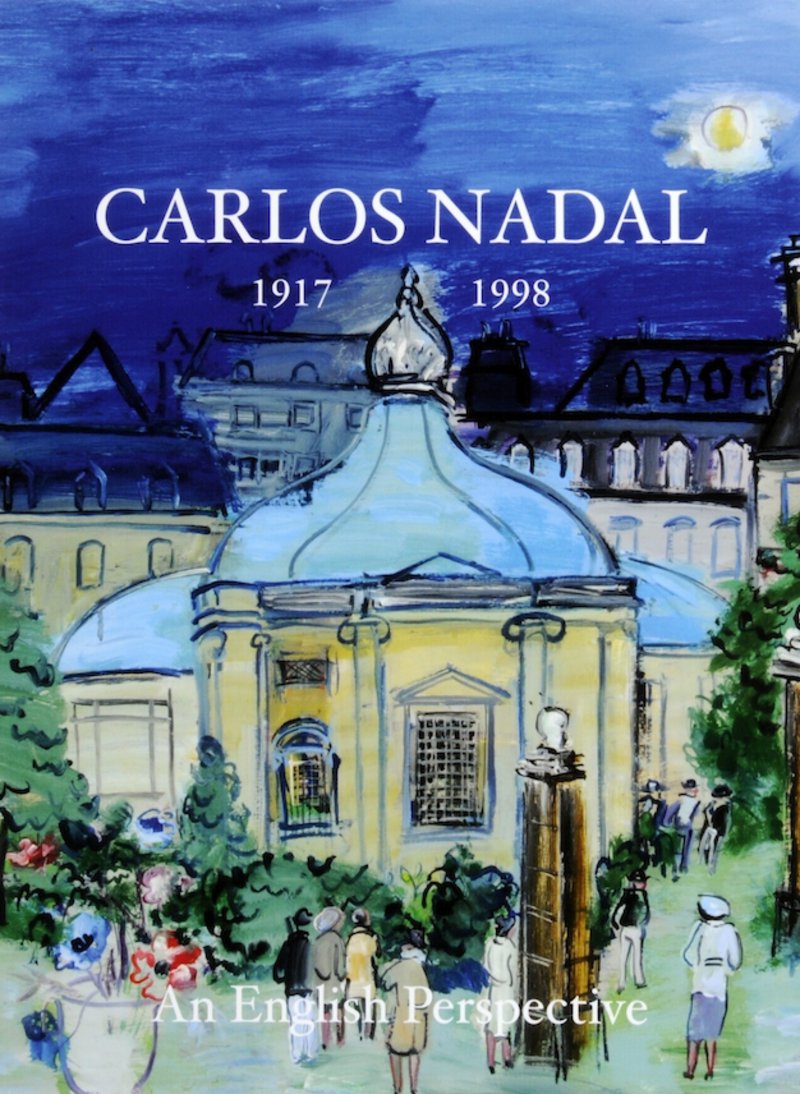

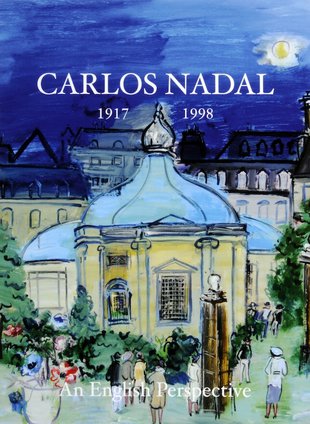

Other sections cover the Theatre, Cafés, Models, Sailing, Country Views and Rooms. The book is completed by exhibition posters and book covers, photos of Nadal and his family, a bibliography and a timeline recording the major events of his life. It gives a thorough overview of Nadal's life and work. It is not the first book that Tillington Press has devoted to him: in 2010 it published Nadal. An English Perspective.

Nadal's work bustles with movement. None of his landscapes or still lives are actually still. His way of expression is swift, using colour and strong lines rather than precise realism. There is no long, subtle build-up of nuance in his drawing/painting. Its virtue lies in its energy, as his joie de vivre explodes onto the page.

Carles Nadal (1917-1998)

Like so many of his generation, Carlos Nadal (1917-1998) was marked by war and exile. Despite family tragedy and poverty, he became a successful painter, whose work is flooded with vitality expressed in rich colours.

He was born to émigré Spanish parents in Paris. His father, Santiago, was Aragonese and his mother, Maria, from Morella, in Castelló. They ran a commercial art studio (an atelier) and knew many of the great painters of the start of the 20th century, when Paris was the world's art capital.

Conscripted into the French Army in World War One, Santiago was poisoned by mustard gas. Unable due to his poor health to maintain the studio, the family with three young children moved to Barcelona in 1921, settling in Gràcia.

Nadal's father died in 1931. Nadal studied art at La Llotja, a school that prioritised drawing and yet reflected the Catalan ferment in the arts, which did not yet distinguish between art, crafts and architecture in the artist's education. While he studied his passion, Nadal designed cinema and theatre posters to help support his impoverished family.

He volunteered to defend the Republic against the military revolt of 1936 and fought on the Aragon front. In 1939 he crossed the French border with the defeated army and was confined in the St. Cyprien concentration camp on the beach. He bribed guards with their portraits drawn on scraps of paper and cigarette packets. After five months, he escaped and returned to Spain. He was again imprisoned briefly, though he was a member of no political party.

He returned to his studies in 1941, becoming a pupil of the landscape painter Josep Amat. Stifled by post-war Barcelona, in 1946 he won a scholarship from the French government to study in Paris, where his mother had returned at the end of the Civil War. “In Barcelona he learnt the craft of painting, but in Paris he discovered what he wanted from painting,” his son Alexandre summarised.

Post-war Montparnasse was an explosion of freedom and new ideas after Barcelona. There, too, he met a fellow art student, the Belgian sculptor Flore Joris. They married in 1948 and moved to Brussels. In Belgium, Nadal found success as a painter. And he won a competition to design the Belgian Congo Pavilion for the 1958 Brussels World Fair. He visited the Congo before painting the Pavilion's giant frescos. Other design commissions followed. They were years of economic security for the family, but Nadal wanted to paint and at the end of the 1960s they returned to live in Catalonia.

In 1959 Nadal had had a summer studio built in Sitges in a modernista style, with two working spaces, for Flore and himself. There they settled for the last three decades of Nadal's life. Flore died in 1988 and both are buried in Sitges cemetery.